In 1881, cableships Dacia, Silvertown and Retriever (1) commenced laying a series of cables for the Central & South American Telegraph Company, a predecessor of the All America Cables. Manufactured by the India Rubber Gutta Percha & Telegraph Works Company, the cable system ran from Tehuantepec, Mexico – La Libertad, El Salvador – San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua – Puntarenas, Costa Rica – Balboa, Panama – Buenaventura, Colombia – Santa Elena, Ecuador – Payta, Peru – Chorillos, Peru.

Reports in The Telegraphic Journal and Electrical Review on the progress of the cable from 1881 to 1883 may be seen on this page. See also the official record of the laying of the cable, and the story of cable engineer George West's repair of the cable in May 1883.

The project was finished in August 1882, and the event was reported in various newspapers as follows:

PANAMA

AUGUST 19, 1882

SUCCESSFUL COMPLETION OF THE WEST COAST CABLE.

On Friday, Aug 4th, the steamships Silvertown and Retriever started from Pedro Gonzalez Island in the Bay of Panama—the former ship paying out cable to complete the section between that Island and San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua. Mr Parsoné, General Agent of the West Coast of America Telegraph Company, having volunteered to take charge of the temporary hut on Pedro Gonzalez Island for the electrical tests etc., necessary during cable laying, his services were accepted by Mr R K Gray and with Messrs. Bailey, Norton and Phillips, he remained at that island, roughing it, until Sunday last when, learning by cable that work at sea had been completed, they returned in the P.S.N. Co’s tender Taboguilla, which went to the Island to bring them to Panama.

The steamship Silvertown returned as already announced, on the 17th inst. with Mr R K Gray on board, after having successfully completed the section to San Juan del Sur. The final splice of this section was slipped on the tenth—thus completing the whole telegraphic system of the Central and South American Telegraph Company. Few persons are aware of the extent of this system, which runs from Lima to Payta, Peru; from Payta to Santa Helena, Equador; from Santa Helena to Beunaventura, Columbia; from Beunaventura to the island of Pedro Gonzales, and thence to Panama; from Pedro Gonzalez to San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua; from San Juan del Sur to La Liberatad to Salinas Cruz in Mexico. From Salinas Cruz a land wire crosses the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and a cable thence from Coatzacoalsco to Vera Cruz, Mexico, places the line in connection with the United States and the Old World.

The total length of electrical cable connections completed by the Company amounts to three thousand one hundred and seventy knots—a figure which proves the enormous amount of work which has been rapidly and successfully performed.

A flaw discovered in laying the Pedro Gonzalez and San Juan del Sur section was easily removed within twenty four hours of being discovered, and perfect communication through the whole line was re established within twenty four hours. The electrical tests were so accurately made, that they located the flaw within one knot of its actual position. The main cable was at once grappled for and picked up in seven hundred fathoms of water, reeling in was commenced, and very shortly afterwards the defective piece was made good. The cable that was picked up was found within 500 yards of its location on the cable company’s charts—a circumstance which proves the wonderful accuracy which must be observed by all concerned in such an extremely scientific and costly work as that which has now been successfully and happily terminated.

The undertaking has been a great one.

Now that it has been happily concluded, the few drawbacks which have been encountered having been overcome by forsight and knowledge, and the work having been performed on a coast hitherto almost if not entirely unknown to the promoters of cable enterprises, Mr Robert K Gray and everyone connected with his staff and the vessels, must feel satisfied with the satisfactory results which have attended their labours.

The Salina Cruz (Mexico) office in 1882

All America Review May 1928

Site visitor John Cunningham notes that his great-grandfather, James Bartlett, worked for All America Cables in Mexico, where he met his future wife. In the same issue of the company magazine that was the source of the photograph above, Charles E Cummings, who started at All America in 1881, reported: "Another old-timer of pleasant recollection, who got his start at Salina Cruz, and who recently passed away in New York, was "Jim" Bartlett, the envy of his fellows as a cable operator and penman." |

THE GAZETTE, MONTREAL

SEPTEMBER 25, 1882

Union of the three Americas by Telegraph.

By Wolfred Nelson

(Our Resident Correspondent)

Panama, September 16th, 1882.

The cable steamers Silvertown and Retriever have returned, and are now anchored in this Bay, their work having been completed in the most satisfactory manner. The cable work and direction of the whole enterprise has been under the immediate care of Mr Robert Kaye Gray, FRGS, chief engineer, representing the contractors, The India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Works Co, limited, of Silvertown, London, England.

Mr Joseph B. Stearn, a celebrated American electrician, and the inventor of duplex telegraphy, is here representing the new cable company, whose title is the Central and South American Telegraph Company. Mr Stearn, by the way, is well known “at home” in Canada. His system is used by the Montreal Telegraph Company. He and Mr Badger of the Montreal Fire Telegraph Department, worked together before Mr Badger left Boston to take up his residence in Montreal. Mr Stearn has taken the position of General Manager of the new enterprise, pro tem. When all is complete he will hand over his charge to the President, and return to England, his present headquarters.

The cables laid by the International, Dacia, Retriever and Silvertown for the new company by the contractors fleet, comprise some 3,200 miles of marine cable. The C & SA Telegraph Company also have 313 miles of land lines working in connection with their cables, as above.

The new company is American and has its head offices in New York. The lines of the Mexican Telegraph Company run from Galveston, Texas, to Vera Cruz, Mexico, where the cable of the C & S American Telegraph Company commences. The stock in both companies is nearly all held by the same shareholders. One president, Mr James A Scrymser, of New York, acts for both companies. The cables of the C & S American Telegraph Company extend from Salina Cruz, in the gulf of Teuantepec, Mexico, on the Pacific side to Lima, in Peru, there the cables of the West Coast of America Telegraph Company begin, and extend to Valparaiso, Chili, to be described later.

The connection of the Central and South American Telegraph Company, with other ocean and land lines, will give a total mileage of over 20,000 miles, in Mexico, Central and South America, and with the Transcontinental line, an additional 6,250 miles, or in all, 26,250. Here is a truly vast system of telegraphic connections just completed.

The three Americas are united by the cables of the Central and South American Telegraph Company for the first time. All honor to American enterprise.

Previous to the inauguration of the new company there was no direct communication by telegraph between these countries as stated. For example, to send a message under the old regime to South America, it had to be sent from New York, via, Newfoundland to England; thence by land lines and cables to Lisbon, Portugal; thence by cables to Madeira and the Cape de Verdi Islands and from the latter to Pernambuco in Brazil. It will be seen that a message had to cross the Atlantic twice ere reaching the Atlantic coast of South America. Once there it could be sent up and down the coast by the cables of the Brazilian Submarine Company, from Para on the north, the neighbour of French Guinea, to Montevideo, in Uruguay , on the south; thence by a land line across the continent via Rosario Mercedes, and Mendoza in the Argenteuil Republic, to Santiago and Valparaiso, Chili; thus reaching the Pacific, or the west coast of America, whence messages could be sent as far north as, Lima, by the west coast of America Telegraph Company, an English Corporation, whose manager is Edward Wm. Parsoné.

To fully illustrate how awkwardly people were placed in Panama and Callao, when they had to cable to each other, the following will show. Let us suppose that A of Panama had to cable to B of Callao, distant only eight days by the English steamer. His message had to cross the Isthmus, thence to Jamaica, Havana, Key-West to New York, thence via Newfoundland to England, over the continent to Lisbon, thence to South America, arriving at Pernambuco, thence via Montevideo across the continent to Chili, thence up the coast to Callao, at an expense of nearly $13.00 a word. It would have to travel over 14,000 miles of cable and 7,680 miles of land wire, in all nearly 22,000 miles- pretty well around the world. This was not only tedious and very expensive, but at times almost useless, owing to the land wires in South America being in a chronic state of “down”, so that the mere paying for a message, was often the easiest part of the whole affair. Such was not the exception but the rule. Important messages often had to be sent on horseback across the wild pampas of South America. Now it is but fair to assume, that under the new era, these annoyances have been relegated to the past, and the Three Americas are in direct electric connection. Messages can be sent by either North or South America, or the Isthmus of Panama, to Europe, or in a word, all over the inhabitable globe.

Now, how is all of this done under the new order of things? Simple enough. A cablegram, for either Mexico, Central or South America, on the Atlantic or Pacific side (in some places) can be handed in to the office of the Montreal Telegraph Company “at home” or to any of the Western Union offices in the United States. It will then be forwarded direct to Galveston, Texas, thence by the cables and landlines of the Mexican Telegraph Company, to Vera Cruz, Mexico, Atlantic side; thence it travels over the first section of the Central and South American Telegraph Company’s cable to Coatzacoalcos, a small Mexican village, situate at the mouth of the river of the same name, a distance of 138 miles, in the Gulf of Mexico; this section was laid by the contractors steamer International, in March 1881. The land line starts from Coatzacoalsco, and crosses the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a distance of 195 miles, terminating at Salina Cruz. Mexico.

Here the company are credited with having profited by having the experience of the Western Union Telegraph Company, whose lines in the early days of telegraphy were of small wire, No 16, these were often cut on the “wild prairie” by the gentle savage of Uncle Sam's neglected family. A number 9 or a layer wire was then employed that was practically useless to the redskin. The C & S American Telegraph Company here, “give one better” by using a No. 8, a larger wire having a greater message capacity.

To return to Salina Cruz. It is the northern terminus of The Central and South American Telegraph Company on the Pacific, and from it the first section of cable runs south, a distance of 435 miles to La Libertad, in Salvador. At the latter port the company makes its first connection with the telegraph system of Central America. The names of the Central Spanish-American Republics now in direct communication with each other are as follows:-Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The second section extends to San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua a distance of 2,694 miles and from the latter place to the island of Pedro Gonzales, the distance to the island being 671 miles. The island of Pedro Gonzales is in the Pearl Island group, nearly opposite the Isthmus of Darien. The Pearl Islands are known the world over for producing the largest and most beautiful pearls. The Isthmus of Darien produces - well, crocodiles, india rubber, big trees and a fever that has been celebrated since the days of Patterson’s colony. The name of Patterson is well known to English readers as the founder of the Bank of England. His famous Darien scheme received the Royal sanction in 1695. Patterson landed 1,300 men in Panama, nearly all Scotchmen, who proceeded to the Darien to found his new Edinburgh. Between fighting the Spaniards, destitution and fever, the little colony was all but “wiped out”. History informs us that but thirty reached Scotland, and of them says, “they were too weak to weigh the anchor of the vessel which was to carry them home, and had to be assisted in their departure by the Spaniards. Vide Macaulay et al.

From Pedro Gonzales Island a section runs in back of the island of Tobago, one to Brighton, a distance of 49.4 miles to the city of Panama. The landing of the cable here, and its having been buried in trenches on it’s way to the company’s Panama offices, has already been referred to in the Gazette's Panama correspondence. At Panama it connects with the Panama Railroad Company’s telegraph across the Isthmus of Panama to Colon

(vel Aspinwall) on Navy Bay, Atlantic side, thence by cables of the West India and Panama Telegraph Company, an English corporation, to all its important West Indian Islands, as well as with British Guinea or South America. Messages can also be sent by the same company via Cuba and Key West, to Europe as already described.

From Pedro Gonzales Island, another section of cable runs, a distance of 358 miles to Buenaventura, where it connects with the land system of the Columbian Government, estimated at 3,000 miles, the objective point of the latter being Santa Fe de Bogata, or the capital of the United States of Columbia, an all but inaccessible place away up in the mountains, 8,000 feet above sea level. It is more than a “Sabbaths day’s” journey to our Paris.

From Buenaventura another section extends 486 miles to Santa Elena, in the Republic of Ecuador. Santa Elena is nearly under the equator, and is at the mouth of the Guayaguil River; the city of that name is a 111 miles up the river, and is the principle part of Ecuador. A land line runs from Santa Elena to the city, also belonging to the C & S American Telegraph Company. If the writer is not mistaken, this is the first telegraph line in Ecuador – another triumph for American push and investment.

Strange to say, Old England sells the world their cables. We may say without fear of contradiction that England is the sole manufacturer of cables. It is true that there is a manufactory for them in France, but it is a branch house of the company who took this contract; English cable ships, English cables, Englishmen, English capital and English skill are always to the fore. Our American cousins show their good sense in purchasing from our common parent what they cannot produce themselves.

From Santa Elena a section runs to Payta; its length is 222.019 miles. Payta, as the readers of the Gazette are aware, is the principle northern port of Peru, and possesses great commercial importance. A Peruvian land line extends from Payta to Lima, its capital. The latter is wretchedly uncertain (not the capital, the line), and constantly “ailing”. To avoid all difficulties, the C & S American Telegraph Company have added a final section of 552.9 miles to Chorillos, within a short distance of the capital. A land line of the C & S American Telegraph Company, seven miles long, connects Chorillos with Lima. Lima is the southern terminus of the new company, and the northern terminus of the West Coast of America Telegraph Company, the cable of the latter as already said, extends 1,699 miles to Valparaiso Chile, touching the coast of Peru, at Mollendo, Arica, Iquique, and Autopogasta, formerly Bolivia's only seaport, thence to Caldera, Sarena and Valparaiso. From Valparaiso, a land line, that referred to, stretches across the vast continent, thus the Transandine Telegraph Company, is a Chillian corporation. We, of the Pacific coast, thanks to the new company, can now send our messages to Europe by three different routes. If the cables and lines were clear, a message could be sent from your correspondents office in Panama, around the world and back to himself in a very few minutes. It would travel some 26,000 miles via Chili and Uruguay to Europe and back, via Montreal Texas, and Mexico to the Isthmus of Panama. The mind is all but dazed when one commences to contemplate what skill and capital are daily accomplishing in this great world. The tendency of the whole is to benefit mankind and advance civilisation. The millennial period of “plough shares, pruning hooks etc.”, is left for the future, as well as several letters on cables, cable ships and cable laying, to be written in an everyday way, for everyday readers.

THE TIMES.

WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 11, 1882.

By some investments of money, whether the subscribers gain or lose, the world must profit. Among speculation of this infallible kind, the enterprise of the Central and South American Telegraph Company and the Mexican Telegraph Company, referred to by us on Monday, ranks high. They are companies doing business at New York, and under American management. No State aid has been granted, or, so far as we know, been solicited by them. Out of their own resources,, and in reliance on calculation of returns which there is no ground to presume will prove untrustworthy, they have spent nearly a million sterling in filling up the gaps in South and Central American telegraphy. At Callao, the port of Lima, the telegraphic chain up the west coast of South America has hitherto terminated. To the imagination of the engineer, and to the practical judgement of the merchant, the huge stretch northwards, with the republics long ago deserted even by financiers, has been a wilderness isolated from civilisation. Last spring the steamship Silvertown started with several thousand miles of potential lungs and voices for the inarticulate shores of the Pacific. Information we have published shows that the operation is already accomplished; and this morning we record the exchange of congratulations by telegrams between PRESIDENT ARTHUR and the PRESIDENTS of the Central and South American Republics upon the completion of the new enterprise.

The line crossing the continent from Montevideo to Valparaiso, and thence coasting to Lima, is now continued in a series of loops touching at the principal centres of trade to Tehuantepec, three thousand miles away, on the Pacific seaboard of Mexico. Traversing the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the line of the Central and South American company connects with another line at Vera Cruz owned by the Mexican Company. By the Mexican line Galveston is reached, and the rill, as it were, of South American utterance falls into the vast and loquacious sea of Western Union telegraphy, which spreads it over the universe.

Intercourse among the South and Central American States has been confined hitherto chiefly to war. The populations which inhabit them have no easy avenues of communication, and have felt no special desire to construct them. Telegraph stations uniting them at a multitude of points will tempt them to an acquaintance which may lead to friendship. With Europe and the United States of North America the association, though closer than among the several Powers of the South, has been one sided. Europe and the American Union have insisted on bartering their goods in South and Central American harbours. South and Central America possess scarcely any commercial marine deserving the name to reciprocate the visits in the Thames or Mersey, at New York or at Marseilles. New facilities for learning each others wants are certain to cause a vast increase of trade from abroad, and may even stimulate a wish to return the compliment. Additional means of intercourse create a demand in a way which often seems magical. The most slumberous locality, when a railway penetrates it, discovers in a surprising manner that it contains hidden springs of curiosity. The telegraph itself often appears to indulge merely a factitious appetite for news. When tidings are not being looked for, mankind are not extraordinarily obliged to science for bringing in an hour intelligence very possibly vexatious, or, if interesting and instructive had it arrived a month later. But in a telegraphic development like that we have described there is neither mystery or ambiguity as respects the advantages to be gained. without the telegraph the merchant has to take his chance of the market on one side of the ocean and the other. Goods loaded at Liverpool in expectation of a price which alone can make their transmission remunerative may find the demand absolutely satiated, or not to be stimulated except on the most unprofitable terms. A telegraphic line along the shore of Central America will inform the European or Pennsylvanian manufacturer of the exact class of goods likely to meet with purchasers, and the Central American planter of the particular products it is worth his while to raise. Both here and there the supply of wares is practically unlimited. In spite, however, of the enormous distance which separates, the depots, the mutual demand would have been met, if only its nature for the time could have been ascertained. The cost of every voyage which has turned out unsuccessful through ignorance on this side on the wants and wishes of the moment on that, has increased the general difficulties of trade with the richest and least developed of territories on the face of the globe. Telegraph companies can claim no more entire immunity than other financial schemes from unsuspected incongruities of estimates and proceeds. So far, however, as all capital is the property of the world at large, and it returns as a matter of common concern, the world could hardly have employed a million of money more advantageously than in completing, as by the pacific line, a sort of inner circle telegraph to bind South America and the rest of the earth together.

In the circumstances of the Continent a sub marine cable was the natural form a South American telegraph would assume. Land is touched wherever a sufficient need exists, or might apparently be fostered, for telegraphic communication. As new cravings are experienced, the steamships Silvertown and Retriever will be prompt to convey a length of wire landwards to satisfy them. If a republic or city do not display proper recognition of the right of the Central and South American and Mexican Telegraph Companies to hospitable and fair treatment, the companies can lift their connecting cable and leave the offender dumb. The march of submarine telegraph companies is along the deep; and they are more capable than M. de Lesseps of asserting neutrality in international feuds without making a parade of it. They have, however, their peculiar perils. None but the most rancorous belligerent would cut a submarine wire to the injury of the whole neutral world for the sake of incommoding an enemy whom it happened to serve, but submarine telegraphs have other more ordinary and habitual assailants. Marine depths are not all equally hospitable. Not rarely they contain mineral agents which rot away the sheathings. Scientific precautions and careful soundings have begun to diminish the danger. The India Rubber, Gutta Percha, and Telegraph Works Company, which has been laying the cables for the New York capitalists, commenced by analysing the chemical composition of the soil along the route. Yet the inconvenience, while it may be partially obviated, cannot always be banished. Particular tracts of sea and sand are liable to corroding propensities which may be detected but are not to be dispelled. There are mischiefs of human origin still harder to prevent or cure. A merchant captain in ill humour or wantonness will sometimes cut a cable which his anchor has caught. A stolid fisherman thinks nothing of striking a continent speechless that he may disentangle a net without delay. The more completely linked the world becomes by the multiplication of submarine cables the more obviously indispensable it grows that civilised nations should devise how to secure one of the main foundations upon which international intercourse rests. Submarine telegraph companies are mere purveyors and contractors for work which modern existence requires to have done. States cannot too soon acknowledge the necessity of shielding submarine telegraphs by international sanctions, and must find means for applying them. The Companies would prefer that states should take the responsibility upon themselves for guarding the wires and punishing malicious harm to them. As there is not much likelihood that the public will accept the burden on behalf of property primarily private, the best available alternative might be to render attacks upon submarine wires an offence as punishable in neighbouring local courts as if the deep seas were in territorial jurisdiction. An international conference is shortly to be held on the title of submarine cables to defence, and on the way to defend them. No nation has more reason than the British to concur in the objects which the conference proposes. It is a matter of congratulation that the Government is understood to be most willing to co-operate. All countries are interested in the maintaining unobstructed the channels of telegraphic communication. In degree the interest of Great Britain surpasses that of all besides, on account as well as the quantity of its trade for which submarine telegraphs are the feeders as of the remoteness of the markets with which it principally deals.

Thanks to David Siddle for supplying the text of these articles from 1882 newspaper clippings

Panama Earthquake of 1882 and the Cable

Wolfred Nelson, the Panama correspondent of the Montreal Gazette, who wrote one of the articles above, later wrote a book about his experiences in Panama. Titled Five Years at Panama, it was published in 1889. In this he describes a severe earthquake which struck Panama on September 7, 1882, which caused much damage on land and broke the cable.

On the morning of September 7, 1882, I awoke fancying that some one had got into my room in the hotel and had shaken my bed or got under it. I sat up in bed, looked about the room, but could see nothing, for there was but little moonlight. I couldn't understand the thing and stepped out on the hotel balcony. While standing on that balcony trying to account for the cause that had awakened me, the whole building trembled violently, and there was a groaning, crunching noise that I never shall forget.

The balcony that I was on was some forty-five feet above the street. Before the earthquake, and when taking my room on that floor of the hotel, I had looked around to see what to do in case of fire. As soon as the terrible vibration began I stepped over the railing of the balcony and down on the railing of the balcony of the adjoining house, then jumped to the floor, and ran its full length as rapidly as I could. On getting to the end there was a house some ten feet below me. The only idea I had at the time was that I did not like to die like a rat crushed in a cage. Having had no experience with earthquakes within the tropics I didn't then realize that it was one. Following the violent shake all was quiet, and I retraced my steps, climbed up the balcony, and got to the upper balcony of the hotel. My neighbor in the room adjoining mine, was Senor Don Pedro Merino. He had tried to escape from his room by a door leading into the upper hall, but the door was jammed, and he couldn't open it. He came to the door of my room, saying that in all his experience in Central America he never had felt so violent a shock. I went into my room, and as soon as I realized it was an earthquake, I looked at my watch; it was 3:20.

My bath tub had been partially filled with water the night before for my morning bath. The oscillation of the building had thrown a part of its contents over the floor, bottles were knocked down, others were broken, and the ceiling and walls were cracked. In places parts of the former had fallen. The wall of that strong building at the back, where it was fully two feet thick, showed a crack of nearly two inches. We dressed as hastily as possible to get out into the open, and when we got down into the lower hall found the servants gathered there. The building that we lived in was the Surcursale, or annex of the Grand Hotel, and was in the highest point of the city. Hence it felt the vibration more than buildings lower down. When we found the Colombian servants they were sadly frightened. It would seem that when the first shock came they opened a front door to rush out into the street, but did not do so as the tiles on the house came down in a perfect shower. Immediately following the shock and before we had walked down to the main plaza, the whole city was alive with exclamations of terror, and the streets were full of excited people, many of whom had candles. We got into the plaza a little after half past three—it doesn't take people long to dress when earthquakes are about.

I shall never forget the scene in the plaza. It was black with people who had reached there in safety, and had got in the open and away from buildings that were expected to fall. There was still a little light, and the moon was in its last quarter. The hum of voices there and the excitement was something astonishing. There they were, people of all classes—black and white—some dressed, and some very hastily dressed, and some had brought chairs with them. An elderly lady belonging to one of the oldest and most distinguished of Colombian families was found dead sitting in her chair. It was an old case of heart disease, and it simply required the excitement to kill her.

The upper part of the wall, making the front of the facade of the Cathedral, had been shaken into the plaza; huge masses of masonry had fallen down upon the stone steps in front of the old building, breaking them and driving them into the earth. The Cabildo, or town hall, was wrecked. The lower part was a cloister of the old time Spanish type, with columns and arches. Above there had been another series of arches giving a front balcony with its roof. The latter with the columns had been thrown into the plaza, and many of them were broken into fragments, while a part of the main roof of the building had been shaken down and off. Its front was wrecked. The Canal company's building, while it showed no visible damage, was badly cracked, and a repetition of a shock of equal intensity probably would have thrown part of it down. As soon as a little daylight came in, it was found that the arches of the Cathedral had been badly damaged.

With the return of daylight all seemed to recover some courage, for if there is anything that unnerves one, it is to feel the earth violently tremble under one, and hearing buildings groan. There was a vast deal of damage done in the city; walls had been thrown down, and there had been some accidents. A doctor of law in his fright had jumped from a balcony and broken his leg. In a house on the Cabe Real a man and his wife had left their bed just as the upper wall of an adjoining building came through the ceiling, burying it under the débris. I should also say that at the Cathedral a number of the Saints had been shaken from their niches in its front. The old tower of the Chapel of Ease, opposite the Quinta of Santa Rita, had been shaken down, burying a wooden shanty from which the family had just escaped. The only fatality in the city of Panama was that of the old lady who died in the plaza.

As the morning advanced we all became more collected, and speculation was rife as to the exact starting-point of the earthquake, the majority fancying that the wave had travelled southward from Central America. At that time the cable ship Silvertown was in the harbor, a huge vessel belonging to the India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Company, of London, England. She had just completed the laying of the cables of the Central and South American Telegraph Company, from Peru to the Isthmus and thence to Mexico. The chief of the cable staff, Mr. Robert Kaye Gray, F.R.G.S., was on shore. After hearing all that was to be ascertained regarding the earthquake and examining a number of buildings, together with my quarters in the hotel, which he considered had suffered most, he expressed the opinion that its origin was local. The cable of the West India and Panama Telegraph Company from Colon to the West Indies, and thence to Florida in the States, had been broken. Thus we were shut off from that side, and could get no news from the outside world. The Central and South American Cable had been successfully laid but it still was in the hands of contractors, or Mr. Gray's company.

The interests of the Cable Company proper were represented by Mr. J.B. Stearns, a gentleman whose patent for duplex telegraphy has made him well known in the scientific world. Thanks to the courtesy of these gentlemen, I was enabled to send a press despatch—the very first—over their cable to New York. I sent the Herald four hundred and eighty-five words. Later on we got information as to what had happened in other places. The crews on the vessels at anchor off the islands of Naos and Flamenco were roused from their sleep—such as were not on duty—and supposed that the vessels had grounded or were dragging their anchors. The island of Toboga, nine miles from Panama, had had a severe shaking and part of a substantial cliff had fallen into the sea. Some people came over to Panama from the Colon side, and then it was that we learned that the shaking in Colon had been even worse than on our side. From the city of Colon to Baila-Mona the Panama Railroad had been rendered almost useless. In places the road-bed had sunk; in others it was completely thrown out of line, and for two and twenty miles this condition of things obtained. The long bridge, of over 600 feet, at Barbacoas was thrown slightly out of line.

In speaking of Morgan and the river Chagres, reference has been made to Cruz of those days, or Las Cruces of to-day. The latter settlement is not very far from one of the central railway stations on the Isthmus. Previous to the earthquake there had been a substantial stone church there. That building literally had been shaken to pieces. Its ruins were photographed by M. Demers, chief of the photographic service of the Panama Inter-oceanic Canal Company. Not a piece of the wall four feet high was standing. We learned subsequently that several lives had been lost in a small village between Colon and Panama.

With Colon on the Atlantic my readers are tolerably familiar. The majority of its buildings were of wood. The violence of the shock was such that piles of plank, put up in the usual way, were shaken down and, bad as our experience was in Panama, certainly the earthquake violence there was greater. It was such that people who attempted to walk, were thrown off their feet. There were also a few accidents. As usual, under such terrible circumstances, the majority absolutely lost their heads. Strong men, who under ordinary circumstances would have undergone almost anything, were as helpless as children. When daylight came upon the scene in Colon, it was found that a great rent crossed the island from near the substantial stone freight sheds of the Panama Railroad Company right along the front street to the earthen embankment connecting the island with the main land. Later on a fissure was discovered running along the right bank of the Chagres. It was traced some three miles and varied in breadth from several inches to a mere crack, closing below in abyssmal darkness.

I was told by Mr. Burns, an intelligent American contractor, who was then mining in the hills between Colon and Panama, that men in his camp were shaken off their feet, and that a mule fell and rolled over and over. That was the earthquake of the first day. The next morning about five o'clock there was another one. I did not dare stay in the hotel, as it was so badly damaged. The lofty buildings practically were abandoned, and all who could go out of town, went out into the open country, sleeping under tents or any shelter they could get. Business was absolutely at a standstill; the sick forgot their illnesses, and the only subject of conversation was los temblores or the earthquakes. A friend, now resident in St. Thomas, had offered me a shake down over the Colonial Bank. While nobody was afraid, the sociability was intense. The next morning, at 4:53, there was a violent shake, and we hurriedly dressed and got out into the street. As usual, the whole town was alive; all of our fears had been reawakened, and a feeling of impending disaster impressed everybody. When daylight came we were out in the Plaza St. Anna, and well do I remember the first pencillings of light along the horizon and the quiet delight with which we welcomed it.

While severe earthquakes during the day are bad, in the darkness of night they really are appalling. On the second night after the earthquake, I accepted an invitation from .another friend, whose building was not so lofty as the bank, in which I had passed the previous night. He adopted an ingenious device, well known in earthquake countries. In subsequent press letters I dubbed them "Stearns' Earthquake Detectors." He stood two soda bottles and a number of mineral bottles on their mouths. Any shock would upset them and give an alarm. The tremor that night was but a slight one, and on the third night I slept in the hotel proper—in a way, for we were all so unstrung by the intense nervous strain, that restful sleep was out of the question. The building of the Cable Company, in which I passed my second night, was so damaged that one of its walls subsequently had to be stayed up and secured.

At that time the Panama Canal Company had a maregraph at Colon, and it was found that there had been a species of tidal wave, as indicated by the perpendicular tracings made by that instrument. As I have stated, the Panama and West India Company's cable was broken, and the other cable was not open to the public as it had not been transferred by the directors to the company, and consequently we were shut off. There is a general impression that “news travels by post,” but, as an exception to the rule, I may here state that, upwards of a month subsequently, we received information on the Isthmus to the effect that a tidal wave had swept some of the islands on the Atlantic side in the vicinity of the Gulf of Darien. It swept across them, washing away ranchos and inhabitants, and some sixty-five people perished. But, as I have said, we only learned this a month later. It would seem that the centre of seismic disturbance had been a little to the south of the Isthmus of Panama and almost opposite the old Isthmus of Darien. Hence, the tidal waves that swept the islands in the Archipelago in that direction, and the earthquake wave which so violently shook the Isthmus.

I kept records during the “shakes.” After the fifth day there were no strong, but many minor, ones. I have notes and records of them by the dozen.

The third violent shock was about the fourth day; it occurred about eleven o'clock, P.M., when, in common with others, I was tremendously pleased to get into the Plaza Triompha and out in the open. The only idea that seems to actuate one under such circumstances, is to get away from buildings, or anything that can fall upon one. While we were in that Plaza—everybody talking to everybody, for on such occasions formalities do not exist—there were violent shakings, and in a street near us there was a rush and considerable excitement caused by a hysterical woman's shrieking.

On the afternoon of that day an old acquaintance of a friend of mine had visited his house, and it being late at night asked the privilege of staying there. She was allotted a room and a hammock. On the morning subsequent to this last shock they found she was not awake, and thought she had overslept herself. Later, finding she did not move, they approached her hammock and found her dead—another case of heart disease, her death being caused by excitement.

While making no professions of bravery, I have yet to learn that I lack the courage common to most men, but for weeks after that experience when in the quiet of my room at night, surrounded by cracked walls, whenever I allowed my mind to dwell upon the awful scene, I would shiver from head to foot. It was a fearful experience. If there is any one thing that utterly unnerves one, it is an earthquake of that type—one that will shake buildings to pieces, partially destroy a railroad, and create the havoc and destruction of that terrific earthquake of the 7th of September, 1882.

As soon as it was possible to collect reliable data I sent a series of letters to the Montreal Gazette, and they were published in extenso. Following their publication there was a lot of scientific discussion in the Old Country, as to what would be the effect of an earthquake on a completed canal. Scientists took the ground that the embankment on the side whence the wave came, would suffer most, and that an earthquake of that violence would seriously damage any canal.

As soon as possible I instituted careful inquiry as to the history of the early earthquakes on the Isthmus, for, when I became a resident there, I had no knowledge of earthquakes, nor had I ever heard of any in connection with that neck of land. From the typical “oldest inhabitants” I learned that the earthquake in the fall of 1858, that had so damaged Carthagena on the Atlantic, had done a great deal of damage in the City of Panama. I also learned that upwards of a century ago the country had been terrifically shaken from Santa Fe de Bogota to Panama, and that about one hundred thousand lives had been lost. Some ten years prior to the earthquake of 1882 there had been a violent shock, the greatest force being felt in the State of Antioquia, to the south of the Isthmus. A pueblo, or village called Cucuta, was literally shaken down and upwards of five thousand people lost their lives [Star and Herald, Panama, 1878]. It will be seen that earthquakes in Colombia are not modern inventions [“Humboldt's Travels”].

A remarkable feature in connection with that earthquake period at Panama must not be overlooked. It would seem that my despatch to the New York Herald was cabled abroad, and it all but produced an earthquake among M. De Lesseps' shareholders. He at once informed the world that there would be no more earthquakes on the Isthmus. Strange to say, despite the utterances of this celebrated man, the earthquakes kept on, to the unstringing of our nerves and to the contradiction of even so distinguished an individual as Count Ferdinand de Lesseps.

Another statement in connection with this and I have done. Such of my readers as are familiar with the historic Paris Congress of May, 1879, that was called together to consider the Panama Canal, will remember that M. de Lesseps denounced any Nicaragua route as impracticable, owing to the fact that it was a land of earthquakes, and that the only route was that at Panama. The only interpretation that one can place on such a statement is, that M. de Lesseps had settled on the Panama route before calling his scientists together. And such was the case. That he, as an intelligent man, could have made such a broad statement, savors of absolute ignorance regarding the past of the Isthmus; as that indefatigable traveller and great authority, Humboldt, refers to the peculiar formation of parts of Colombia and the terrific cataclysms that must have obtained there in early days.

Within the last few days [April, 1888] I note that the adjoining Republic of Ecuador has been violently shaken by earthquakes, and so violent were they that they produced a panic among the people. What effect such earthquakes would have upon a tide level canal or any other canal are best imagined, and description is unnecessary.

Text courtesy of University of Michigan via Google Book Search

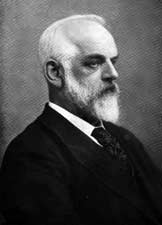

Robert Kaye Gray in 1903 when he was president of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE).

Image from Page's

Engineering Weekly. |

Robert Kaye Gray of the cable company, mentioned in Nelson's book, was prominent in the telegraph and electrical industries of the time. He was born in Scotland in June 1851, and died in April 1914.

He lived for many years in Woolwich, close to the centre of the cable industry in London, where he was Telegraphic Engineer-in-chief for the India Rubber, Gutta Percha and Telegraph Works Company. In 1881 and 1882 he was in charge of the laying of the Central & South American Telegraph Company's cables, described in the articles above, which brought him to Panama in September of 1882 in time for the earthquake.

In October and November of 1883 he was in command of the expedition to connect Cadiz with the principal islands of the Canary Group,

the cable being laid by CS Dacia and CS International.

In 1889 Gray was elected to membership of the Royal Institution, and in 1903 he was President of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), London. He was also involved with other professional and educational institutions. |