Introduction: The story has been told many times of the great earthquake of Wednesday 18 April 1906 which leveled most of San Francisco, but the broadside that is the subject of this page, “Wrecked San Francisco” (Number 4), gives an insight into how important the Commercial Pacific Cable was in transmitting to the anxious inhabitants of Honolulu the news of the disaster and the resulting conditions in the ruined city.

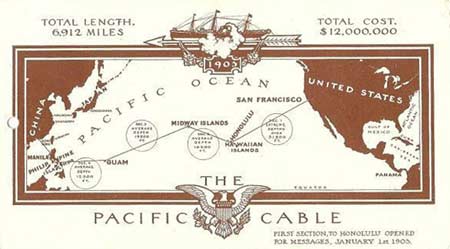

The cable had been opened for service between San Francisco and Honolulu on 1 January

1903, just over three years before the earthquake, and was an essential communications link between Hawaii and the American mainland. At Honolulu, an onward connection was routed via Midway and Guam to the system’s terminus at Manila in the Philippines.

Commercial Pacific Cable route map |

From the Philippines, existing cables of the British-owned Eastern & Associated Telegraph Companies could carry messages to Europe and Britain, and the Atlantic cables could then be used to transmit messages to New York in the event of a problem with the direct link from San Francisco to Hawaii.

This alternative route was to prove useful immediately after the earthquake, when conditions at San Francisco rendered the cable to Honolulu temporarily inoperable. In order to send word to Honolulu, which had no knowledge of the cause of the failure of the cable, messages from the cable staff in San Francisco would have followed a route similar to this:

San Francisco to New York - landlines of the Postal Telegraph Cable Co.

New York to Lisbon via Fayal, Azores - Commercial Cable Company

Lisbon to Bombay - Eastern Telegraph Company

Bombay to Madras - landlines of

the Indian Government telegraph

Madras to Singapore - Eastern Extension Telegraph Company

Singapore to Saigon - French Telegraphs

Saigon to Manila -

Eastern Extension Telegraph Company

Manila to Guam to Midway to Honolulu - Commercial Pacific Cable Company

Total distance in nautical miles, 21,397.

A hundred years later, redundancy and duplication of cable routes are still important factors in the reliability of the Internet today.

The broadside shown below does not have the name of the publisher nor the date of its release. But the content locates it in Honolulu, and from the number 4 at the top and the subhead “Free Advertiser Special,” it appears to be one of a series issued immediately following the earthquake. The broadside has a street view of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company’s office (which was located at 3 Alexander Young Building, Honolulu) with crowds thronging outside the building waiting for news.

A search for a Hawaiian publication with Advertiser as part of its name located the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, a newspaper founded in Honolulu in 1856 and published under that title until 1921. After subsequent takeovers, the paper survives today as the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

In the Advertiser’s issue of 23 April 1906, its editor described how broadsides had been issued free of charge by the proprietors to keep the local population up to date with messages received over the cable as they arrived. At that time, just five days after the earthquake, he said that twenty of these “Specials” had already been published.

Even by 1910 Honolulu had a population of only 52,183, and the Advertiser noted that at the time of the earthquake several thousand of the inhabitants had relatives and friends in the San Francisco area, 2,300 miles away by sea, so there was obviously great concern in Hawaii for their well-being. The Hawaiian Territory was largely dependent on ships from San Francisco for supplies and banks there for financing, so news of the fate of commercial operations in and around the city was also in great demand.

Full details of the broadside and its background are below. Stories from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser and The Hawaiian Star are reproduced courtesy of the archives held by University of Hawaii at Manoa eVols and Library of Congress Chronicling America.

|

After the earthquake struck San Francisco at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday 18 April 1906, all communications from the city were cut, both domestic and international, and nothing was heard in Hawaii until 11:30 pm the next day. In its issue of April 19th the Pacific Commercial Advertiser had this banner headline and story at the top of the front page:

|

HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 1906.

BUSINESS SECTION OF SAN FRANCISCO IS DESTROYED BY AN EARTHQUAKE

Following are all the authentic bulletins received by the Cable company yesterday from the operator in San Francisco:

(1) Terrific earthquake 5:15 this morning. Enormous amount damage. Land line system demoralized.

(2) Call building is now on fire. The fire is only one block away from us in each direction.

(3) Expect to be ordered out any minute. City on fire all around us. Nearest approach a block away.

(4) The Call building is wrapped up in flames. Everything burning. Palace hotel burning.

(5) You may lose us any minute. Constant quakes. Martial law declared. Water coming up Market street.

(6) Preparing to move. Street looks doomed. Have all small stuff loose, ready to move but unable to get a team.

(7) Forlorn hope. We are forced to close down now. Electric light and gas have failed. Plaster falling in office. Water main destroyed at first, but supply obtained.

Later—Abandon office now. Good bye. |

The newspaper also reported that

The following day, in its issue of April 20th,the Pacific Commercial Advertiser described how the Commercial Cable Company’s staff had rescued what equipment they could from the now-destroyed cable office and were setting up a station at the cable hut on the beach near Clilff House:

BRAVE MEN IN SAN FRANCISCO ARE NOW

TRYING TO ESTABLISH CABLE COMMUNICATION

The long suspense has been broken. San Francisco and California are once more in touch with the world. The story of the great disaster will come in its harrowing details. The news printed this morning puts the stricken people within the reach of human sympathy.

At 11:30 last night the following service message was received by Cable Superintendent Gaines, from the superintendent in New York:

“Our San Francisco superintendent is now at the hut. They are trying to get a battery connected up with the cable.”

That meant that the long tension would soon be broken.

“That cablegram is doubtless several hours old,” said Mr. Gaines, in repeating this message to the Advertiser over the telephone.

As the message reached Honolulu at 11:30, it must have been not much later than nine o’clock. The message being several hours old when it reached Mr. Gaines, as he says, it follows that the work of connecting up a battery had then been under way for several hours.

The relieving feature of the message lay in this, that it showed that, whatever the nature of the calamity that has befallen the California mainland, there were still men living in San Francisco who were trying to get into communication with the outside world.

It showed, moreover, that communication with San Francisco had been secured by the New York cable office. And that was much—how much, the people of Honolulu who have lived now through

forty-eight hours of dreadful suspense can appreciate.

As news started to come in over the cable on April 20th, the Advertiser also began to publish a series of free broadsides for public distribution, of which this is number 4. The tagline reads “Free Cable Specials as Fast as News Arrives.”

4

Wrecked San Francisco

Free Advertiser Special

Latest Cablegrams

(Approximate size 22½" x 10¾",

570mm x 270mm, unevenly trimmed) |

The broadside is undated, but the line below the photograph reads “Despatches up to 11:50 A.M.” and the next-to-last message is datelined “San Francisco, April 20, (11:50 a.m., Honolulu),” so the publication date was 20 April 1906.

The sheet also includes a message sent by Clarence Mackay of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company to the Merchants’ Association, which was received in Honolulu on April 20th. A story in The Hawaiian Star adds the information that Mackay’s cable was dated New York, April 20, 2:45 p.m. [8:45 a.m. Hawaii time] and came via Europe.

The broadside notes that some paid messages had arrived from the United States via Manila, having taken a very long route around the world in the absence of the direct link from San Francisco. Following that, some cable company service messages were received from an operator in San Francisco who is described as being “in an excited frame of mind when he was tapping the keys.” The operator also reported that to stop the spread of fire, “the cable office was dynamited and we are now sending from the hut.” Conditions sounded very bad indeed, but the cable operators kept working, which was common practice during disasters of all kinds.

In the Advertiser’s issue of April 21st, the front page story, with the headline “Cabled Story of Disaster,” is on the restoration of cable service from San Francisco. It repeats much of the information from the previous day’s broadside number 4, and leads off with this note on the “special leaflets”:

With the opening of the cable to San Francisco yesterday morning came the service messages of the cable company, which were given out by the cable people and printed in the free special leaflets of the Advertiser as fast as they came and circulated on the streets.

Here is the text of the main section of the broadside; the messages as received are indented here for readability:

DESPATCHES UP TO 11:50 A.M.

With the exception of a long cablegram to H. Hackfeld & Co, from their agents in Bremen, and one of directly opposite tenor to a Mr. Reynolds, a guest at the Hawaiian Hotel, the only news received today is what the “service” messages contain.

Following is the Hackfeld message:

“By tremendous earthquakes, followed by immense conflagran a great part of San Francisco has been destroyed. This is especially the case of the business section. Chinatown and all of the large hotels are apparently destroyed and many lives are lost. Saving other parts of the city seems difficult as the waterworks and pipe lines are damaged. Miners’ powder is being used to blast buildings with view to checking progress of the fire. Exhausted; situation is desperate. Oakland is seriously damaged. Santa Cruz, Monterey, Gilroy, Hollister, and Santa Rosa destroyed and many places throughout California are damaged and many lives have been lost. Light shocks continued throughout yesterday. Spreckels’ refinery is destroyed.”

J.F. Hackfeld immediately made this public and a stream of people, anxious for news, coursed down Fort street, to the firm’s offices. The excitement which followed the receipt of the news exceeded that of the first day, but there were people who questioned the authenticity of the message, because it came from Bremen and via Manila. The sugar factors had each cabled yesterday and with the exception of that to Alexander and Baldwin, published in the Advertiser this morning, no answer had been received. For that reason it was thought the cable was not correct.

But doubts were wiped out when at 11 o’clock the cable office announced the receipt of service messages.

The groups that had assembled at intervals on the streets scattered toward the cable office where the messages were posted on the window as quickly as received. No reference is made to conditions outside the city and apart from that practically all of the statements in the Hackfeld message are verified.

Crowd in Front of the Cable Office |

The following was received from the Cable Company’s New York office via Manila:

“Oakland expects to open an office in the burned district today. City is destroyed and messages will be delivered to applicants only.”

This was followed an hour later by another service message describing the situation. It came from the operator, the only person to send a message and consideration must be given this fact. He telegraphs as he saw things or heard of them and was in an excited frame of mind when he was tapping the keys:

“The earthquake was the worst in the history of the State and many buildings were thrown down. Immediately fires started in a dozen different places. The breaking of water mains precluded the possibility of assistance in this respect and the fire spread like a prairie fire with no way of stopping it. Both sides of Market street from the Ferry to Twelfth street and from Van Ness avenue to the bay were in flames and the destruction of buildings was almost complete. At Van Ness avenue it seemed to be blocked. The holocaust enveloped all of the business section and about a quarter of the residence portion of the city. Just now—1 p.m.—the fire is pretty well under control, but many of the churches are destroyed and most of us have lost everything. Where no other means were available buildings were dynamited to get them out of the way and create space to prevent, if possible, further spread of the flames. In sections the fire is burning fiercely. We are five miles from town and a team is an impossibility. Estimates of loss are wild, but conservate men estimate it at $150,000,000.

“The Mission is now burning, but the fire has not reached Sixteenth street. Presidio, as near as we can tell, is unaffected. Hayes Valley is afire west to Octavia street and all property west of Van Ness avenue is safe up to this moment. Between Van Ness avenue and Market street nothing remains but the charred ruins of a once beautiful city. The cable office was dynamited and we are now sending from the hut. Owing to the rising water but one operator at a time is allowed in the building. We are preparing shelter tents. We have food sufficient to last several days.

“The Palace, St. Francis, Flood Building and Emporium are destroyed. Fairmount Hotel is destroyed. Relief is pouring in from all sections to those suffering.

“Oakland and Piedmont suffered light shocks, but the damage is not great, as there is no fire. People are at liberty to leave San Francisco, but no one is allowed to enter and the place is under strictest martial law. We cannot get to town except by going through the hot ruins and to send a message means an expense of $75.00. The journey is made at a great risk of life.

“I am informed that the shipping is damaged, but to what extent I am unable to determine. My family and near relatives are in the country, but whether alive or dead. I have no way of telling.

“Lord! this has been a fierce three days.”

Also of interest is one further message from the cable operator at San Francisco, named subsequently as Superintendent P. McKenna:

WORKED OUT.

The “good bye” message received here from the operator shortly before noon stated that he had been on duty for two days and he was worked out. Was going to take a rest. A man would be put in his place and news would be sent along later.

No reference is made to the loss of life.

The April 21st issue of the Advertiser gave more information on McKenna:

SORT OF MAN M’KENNA IS

McKenna, the cable superintendent at San Francisco who opened up communication from that city with the rest of the world, is a Canadian by birth. He has worked under Mr. Gaines, Superintendent of the local office, and is known among his associates as a man who never tires.

“If there was any trouble at the office, McKenna was sure to turn up and work right along until the rush or trouble was over,” said Mr. Gaines yesterday.

McKenna is about 55 years old, 6 feet 1 inch tall, and is married.

Mr. Gaines stated last evening that McKenna had not only saved all the instruments in the town office, but had got them all safely out to the “hut.” The only thing he lacked were batteries. The instruments saved were those of the elaborate duplex system, as well as the testing apparatus. When one sees the duplex instruments in the local cable office, the wonder increases that McKenna and his men ever transported them across the peninsula. In the local office the duplex system is contained in six booths, each containing ten heavy chests. McKenna also saved a month’s files of messages.

The three stories below, from the editorial page of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser issue of April 23rd, provide some details of the “Special” broadsides. It’s interesting to note that editor Walter G. Smith, a former San Franciscan, commended the Commercial Pacific Cable Company for furnishing free message service to residents of Honolulu, and criticized his competitors for profiteering from the disaster by doling out this news in extra editions at five cents a time. The Advertiser’s own daily edition sold for five cents, but its broadsides documenting the cable message were all free of charge.

THE PACIFIC COMMERCIAL ADVERTISER

WALTER G. SMITH EDITOR

MONDAY APRIL 23

THE ADVERTISER’S NEWS SPECIALS

Fault has been found with the Advertiser for issuing free news bulletins concerning conditions in San Francisco.

This paper has no excuse or apologies to make for its action, and would have paid no attention to snarls of other Honolulu papers which did not choose to follow the same course; but when a reputable business man in an open meeting of the Chamber of Commerce makes hostile criticism of the free news service, a statement of the reasons for giving it is due to the public and this paper.

With unparalleled liberality and generosity the Commercial Pacific Cable Company has for five days furnished a free cable service to the people of Hawaii. In fact, with a few exceptions, all that we knew of the San Francisco situation, up to last night, was what the cable operators themselves personally saw and reported.

Several thousand people in this city have relatives and friends in and about San Francisco. They are desperately interested in conditions in the wrecked city. Under these circumstances an afternoon paper began to dole out, a few lines at a time, the free cable service being furnished by the Cable Company, in the shape of five cent extras, which were naturally eagerly bought by those hungry for news at any price. This procedure bid fair to continue indefinitely.

The management of the Advertiser believed then and believes now that if the press of this city had made common cause and bled the people of their own community for the price of fifteen or twenty extras a day, which was the pace set, when a foreign corporation with but slight local interests, was furnishing a free service, which in cable tolls alone was worth thousands of dollars, it would have deserved to be branded as a money-grubbing aggregation compared to which Shylock would have been a philanthropist.

The Advertiser thereupon began the issue of a series of free “Specials,” containing all the San Francisco, news obtainable through the Cable Company and the meagre private telegrams which filtered from the stricken city. Twenty of these “Specials” have been already issued, containing all that is known, and they will continue to be issued until news conditions once more become normal and the people of Honolulu are able to communicate for themselves with their friends, and the newspapers through private enterprise are able to get the news themselves.

Just how helpless the people of Hawaii are in respect to getting news is illustrated by the fact that, with the exception of the cable operator, E.A. Fraser is the only civilian who has visited the lonely cable hut at the Cliff House since communication was opened there last Friday [April 20th], until last night, when the Advertiser’s special correspondent succeeded in reaching the hut and sending the messages published herewith.

Further Advertiser free “Specials” will continue to be issued as long as the occasion calls for them. Those who do not like it can do the other thing.

MONUMENTAL JOURNALISM

Once more the Advertiser scores a great journalistic feat. It is undoubtedly the greatest, in respect both of financial outlay and news results, of which Honolulu has ever had the benefit. Perhaps it would not be too much to say, indeed, that considering the comparative number of people reading the language in which the paper is printed within its constituency, no city in the world has ever issued an edition of a newspaper equaling this morning’s Advertiser, in cost and volume of current news contents together.

Not the least part of this triumph of Honolulu journalism is the fact that no assistance was obtained—though sought at great cost—from any newsgathering association, particularly the greatest in the world and the nearest to Honolulu. It is perhaps, too, the first time that the American Associated Press has ever “fallen down on a detail,” as newspaper talk goes, where it was possible to have succeeded. The main part of the work was done at one end by a single newspaper man and at the other end by the staff of this paper. And, as to the Advertiser staff, it met the big story from the cable at the end of a strenuous day in giving the people of Honolulu, promptly as they came, many details of the days situation in the stricken city—the theme of this monumental issue—free as it was freely given out to the community, as well as this journal, through the generosity of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company, together with personal and other intelligence cabled to private individuals and firms.

THE STAR BOYCOTT

The Star announced on Saturday that the newsboys would boycott the Advertiser on account of its free news “Specials.”

Whether by reason of this threat or whether the boys know that the Advertiser is the paper that people want, we do not know; but we do know that about twice as many newsboys as usual were on hand yesterday morning, and, although nearly a thousand extra papers were printed, they were all sold out by half past six. One boy announced his intention of “licking” any other boy found selling Advertisers. The belligerent promptly skedaddled, however, as soon as an Advertiser man appeared on the scene. Boycotts are in order. Next!

I can find no record of how many editions of the Specials were published by the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, but they presumably ceased publication when the Commercial Pacific Cable Company resumed normal paid message service a few days after the earthquake.

The April 24th issue of the paper refers to “free special No. 22”, published the previous day, and on page 4 also has these editorial squibs with some comments on its competitors:

The 22nd Advertiser free Extra came out about the middle of the afternoon yesterday with an exclusive dispatch from the Associated Press. A large number of the Extras went to the country and everybody within reach of the railroad probably saw the news or heard of it by dinner time. A staff member of the Advertiser family went up the road on the 3:20 train with a bundle of Extras for free distribution. Thousands of copies were sent where they would do the most good in town and out

The Star, which felt hurt because the Advertiser got out specials by day, thus depriving “the newsboys” of a nickel harvest, now feels angry because this paper did not get one out Sunday evening after everybody had gone home. Nothing suits our asteroid contemporary these days. Evidently the sudden stoppage last week of skin-game extras gave it an attack of nickelitis swanzymania, a very painful disease of the mouth.

The same page also has two letters from readers remarking on the Specials, and two derogatory comments from competitors of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser: the Hawaiian Star and the Evening Bulletin, these latter missives accompanied by editorial responses.

HOW THE PUBLIC LOOKS AT ADVERTISER ENTERPRISE

Lihue, Kauai, April 21, 1906.

Editor Advertiser: This community, in common with Honolulu and many other places, has been stricken with terrible suspense and anxiety over the distressing reports from the Coast concerning the awful wreckage of the city of the Golden Gate. Several of the leading families here have “loved ones” in San Francisco or the immediate vicinity and their anxiety is almost unbearable. The first message received was a wireless last Wednesday morning at 8 o’clock, which was terribly shocking, and since then, owing to the absence of fuller particulars, the suspense has been almost paralyzing. This morning’s mail contained your “Special” headed “Free,” which was greatly appreciated and for which you deserve our hearty thanks. It was enterprising on your part and tended greatly to alleviate the worst fears, to wit, that the whole city had gone under. As it is, the disaster is terrible beyond expression and we await still further details with hearts full of sympathy for all who may be directly afflicted when the loss of life is more fully known. God grant that it may not be as great as many seem to fear!

Faithfully yours,

JOHN W. WADMAN.

The writer's location on the island of Kauai was about 63 miles from Honolulu, and his mention of news of the earthquake being received as “a wireless” needs some explanation.

The first transoceanic radio service between Hawaii and San Francisco was not opened for service until 1912 (see Robert Schmitt's history below for details). Prior to that, all messages to Hawaii had to be sent by ship (or after 1903 by cable), so the message from Oahu to Kauai must have been sent by a local wireless telegraph service. The Inter-Island Telegraph Co. was incorporated in late 1899, and the firm contracted with Guglielmo Marconi to establish an early experimental system in Hawaii in late 1900, but the venture is reported as having failed in 1902.

However, Inter-Island was subsequently revived. Reports of news from the other Hawaiian islands headed “By Wireless Telegraph” were regular features in the Honolulu papers beginning in 1901 and continuing past the time of the earthquake. In his 1979 paper “Some Transportation and Communication Firsts in Hawaii,” Robert C. Schmitt provides a brief history of the company and notes that “Service tended to be undependable, and the company went through several crises before beginning to solve its more serious technical and financial problems around 1907. ”

BESTOWING CREDIT.

Editor Advertiser: Kindly permit me to make a suggestion to the business men and people of Honolulu, through your valuable paper: and it would be well if both the Chamber of Commerce and Hawaii Promotion Committee were to pass resolutions pertaining to them.

There are four persons, as well as their subordinates, to whom the people in this community have cause to be thankful.

First. Mr. McKenna and his heroic staff in San Francisco, who first gave the news of the awful catastrophe to this city.

Second. Mr. Gaines, superintendent of the cable office here, through whose untiring efforts communication was at last established with the stricken city.

Third. Mr. Fraser, who has worked faithfully in getting all the information possible regarding Hawaiian Islanders and their relatives, as well as all general information affecting these islands.

Fourth. And last, but not least, to the management of the Advertiser, who as rapidly as the news was received, disseminated it gratuitously in a series of specials. This was a most unselfish, public-spirited act, and has earned the praise of all with possibly one exception.

(It seems almost incredible that a member of the Chamber of Commerce, who poses as one of the leading business men in this city, should make an address to that body. accusing the Advertiser of “croaking.” and in general running it down. One might think that this worthy gentleman was the owner of a few paltry shares in one of the afternoon papers. and was consequently doing most of the “croaking” himself.)

A RESIDENT.

FROM THE BEATEN PAPERS.

The morning paper says it has been criticised for issuing its freak free specials.

It is deserving of pity more than criticism. Its struggle with the news for the past few days has been the bombastic cavorting of an alleged has-been that never was.

The greatest news crisis Honolulu has thus far known found every other paper in the city so far outstripped by the modern equipment of the Evening Bulletin that they were brought to a standstill. The people got the news from the Bulletin.

After waiting two days the morning paper found it was so far out of it, and its equipment so utterly incapable of handling the news that the free job office “specials” was the only means of its keeping before the public. As a piece of newspaper enterprise, it was on the border of a country town bazoo. Every newspaperman who knows anything of the business smiles.—Bulletin

[The above needs no comment. All that it requires is the publicity it receives in these columns]

In view of the expressed anxiety of the Advertiser to give the people of Honolulu the news so promptly, why was the news secured through its “monumental feat of journalism” withheld for nine or ten hours—not why was it not given for free, but why was it not given at all? If it was important to the people at 5 this morning would it not have been equally important and valuable at 7 or 8 o’clock last night.—Star.

[It happens that the closing paragraphs of the message arrived after almost everyone had left the streets excepting a few night hawks and the usual number of Star and Bulletin spies who haunt this office in the effort to filch a little news.—Ed. Adv.]

A short report in the April 29th edition of the Sunday Advertiser has this update on Superintendent McKenna at San Francisco, who worked under such arduous conditions to send the messages published in the Specials:

M’KENNA STILL WORKS AT HUT

McKenna, Superintendent of the cable company at San Francisco, who rose into prominence as the man who after working for forty-eight hours with little food and no sleep, sent out news of San Francisco’s plight to the world, is still at the cable hut near the Cliff House. His staff is with him. They are comfortably housed, having a number of rooms in the cable station. McKenna has not been back to the city since the morning of the earthquake.

This letter from a reader, published on May 5th, is not quite the last mention of the Specials. It gives more information on their origins while taking further digs at the Advertiser’s competitors:

THE COLLAPSE OF SKIN-GAME EXTRAS

Editor Advertiser: Some evenings ago a crowd of us stood in front of the cable office anxiously waiting for news of the great San Francisco calamity when a bunch went to the other side and roosted on the Bishop Park fence. Suddenly a Bulletin man burst out of the office in such speed that he drew up quite a following. His paper had been issuing extras all afternoon and telling of its new press and the hundreds it could clip out per minute. It was but a few minutes until the newsboys came flying around the corner crying “Seventh edition extra!” We naturally made a break for them, opening our purses on the way. It was the same old recooked hash, except that it stated: “We have just sent a cable around the world and expect an answer soon.” We adjourned to our roost to wait. Will Fisher told about how the water came up to Montgomery street in his day, etc., and each had something to tell. Presently around came the army of newsboys crying, “Eighth edition extra.” Then another break was made by the anxious crowd only to learn of the speed of the new press and “an answer was expected soon.” When we found we had paid for the great cable to Manila and now for its expected answer, we presumed it was time to go home.

The next morning the cable service was reopened and the Advertiser began issuing Free Specials half hourly and it had the effect of closing the new press so tight that they have not been able to open it with a crowbar since.

KIMO.

Since Assistant Superintendent McKenna played such a large part in transmitting messages from San Francisco over the cable to Honolulu, where they were immediately published in the Advertiser’s free broadsides, it seems appropriate to end with this front-page story from the July 9th issue of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, which reports McKenna’s promotion to Superintendent at the Guam station of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company.

FRIEND M’KENNA FOR GUAM

M’Kenna, the “cable-hut-man,” at left of picture,

who will pass through Honolulu shortly |

McKenna, the “cable-hut-man” who sprang into prominence at the time of the San Francisco disaster as being the cable operator at San Francisco who was first to get news out of California to Honolulu, will probably pass through Honolulu in August on his way to Guam. Mr. McKenna has been the assistant superintendent of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company at San Francisco, and has been promoted to be superintendent Of the Guam station.

Mr. McKenna was in charge of the cable office at San Francisco at the time of the earthquake. He sent out a few brief messages to Honolulu from the Market street office, until flames encroached upon the building and the office itself, compelling the office to be closed and the instruments removed. Then Honolulu waited. The cable line was dumb for a few days. At this end of the line Superintendent Gaines and his staff remained in constant attendance upon the cable instruments awaiting the first sign that communication would be reestablished. Finally signals came over the wire and it was then believed that the San Francisco force was endeavoring to get into communication with Honolulu from the cable-hut near the Cliff House.

Then at last a message came over the cable from McKenna. saying that he and his staff had worked incessantly and now desired sleep. Then the cable became dumb again. When McKenna awoke news of the disaster came in a steady stream from the stricken city. sent by McKenna personally. The whole story was told. at first in broken paragraphs, just as the news reached the sender from the city, for messengers were few and far between and a military cordon surrounding the city prevented people from passing to and fro. Honolulu depended entirely upon Mr. McKenna and he remained at his post, with his staff, day after day and far into the night, sending news of the disaster, all of which was cheerfully given to the public by Superintendent Gaines, gratis, and published and furnished to the public gratis, by the Advertiser, in “Specials,” which were issued as often as there was enough news to be printed.

From the fund which was subscribed to by merchants and citizens generally of Honolulu for Honolulu sufferers, a portion was devoted to a purse which was presented to Mr. McKenna and members of the San Francisco cable staff as a token of the thanks of the people here for relieving their minds of the dreadful suspense.

For one last time in this story, published two months after the earthquake, the paper’s editor could not resist mentioning the “Specials” which had distributed the cable news to the people of Honolulu.

One final note in the Advertiser, on August 23rd, recorded that McKenna had sailed for Guam that day on the US Army Transport Logan. |